On Acre Mill Road, just about 50 yards before Acre Mill House, there is a cobbled lane that starts at the place where James Ashworths Woollen Mill office building used to be. It goes downwards through the trees and behind Springhill villas. The cobbles end at a flat area where Moss Row used to be. You can turn right and continue on the pathway at the side of the river Irwell. The path crosses the river on the small iron bridge, then passes under the Railway bridge and onwards untill it meets Newchurch road next to Stacksteads working mens club. Over the years this has come to be known as 'Shade End'. In fact that's not really correct and I have often thought that we kids playing in Acre Mill Road in the mid 1950s were responsible for distorting the name.

I remember when we were kids playing in Acre Mill Road, the weavers from t' woollen (James Ashworths Woollen mill) used to ask us where we were going and we used to say 'down shade end'. They used to be amused by this and kept trying to correct us, but because of the high buildings and tall trees it was always shaded and dark and we kids just couldn't call it anything else but Shade End.

The fact is that if you walk from where Woollen Mill offices used to be on Acre Mill Road, down the cobbled lane to where Moss Row used to be, you will have been 'downt' shed end'. That is, down the end of James Ashworths weaving shed.

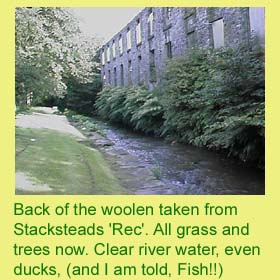

During the school holidays I used to work at the woollen. I was assistant to a chap called Tommy Halliwell who was the Loom-Tackler. The remains of the mill are still there on the banks of the river Irwell. Even in the mid 1960s it was partially derelict. I used to think of it as a cold, miserable place full of out-dated machinery. Now, I wish it had been preserved as a museum.

|

The wool was received in huge bales. It was straight from the backs of the sheep and tangled-up with bits of twigs and things. It was delivered to a small warehouse next to the office on Acre Mill Road. The warehouse was a kind of a loft over the Devil 'ole. Owd Dan used to do the Devilin'. I never really sorted out exactly what the process was for. Few people except Dan ever went into the Devil 'ole. The machine bounced around and made a ferocious noise but more dreadful than that was Dan. He was an unfriendly and constantly bad tempered character. Almost everything upset Dan but his most constant source of misery was his teeth. He had lost them all and had false ones made but he could not come to terms with them, so he never used them. His diet was exclusively Ambrosia Creamed Rice which he ate morning noon and night, direct from the tin. |

|

After the wool had been 'Deviled' it went to the Carding room where an Irishman called Mick McNulty used to run four big Carding Frames which would pull out the wool fibres to get it ready for spinning.

The spinning room was above the Carding room. I estimate that the room was 40 or 50 yards long and there were two spinning frames each one running the full length of the room. The machines were operated by a Polish guy called John Shush. The frames would pull out to the centre of the room and the spindles would rotate to spin the wool then the frames would close-up again as the spun yarn was wound onto the spindle. The machinery was very old and the lubrication systems were basic. There were no drip trays or anything and after years of these machines going to and fro across the room the old floorboards had become soaked in oil. People used to joke that one day they would make good firewood. It actually happened many years later when the room was being used as a discount carpet store.

It was one of my jobs to collect the weft from the spinning room and deliver it to the weaving shed. The weft was in enormous wicker baskets that I had to drag across the oil-soaked floor and then down a stone staircase. The big baskets almost filled the stone staircase. The technique was to run down the steps in front of the basket, hit the wall at the bend, steer the basket round the bend and bounce it from the second or third step onto a hand-cart. If the basket stopped at all on the staircase it would inevitably wedge and everyone (except Dan) would have to get involved to get it moving again.

In the weaving shed there were probably about 16 looms arranged in pairs. I don't think I recall a time when there were more than about 5 pairs running at the same time but still the noise was considerable. The looms were about 15 or 18 feet wide and like all the machinery in the factory, they were driven by line shafts. Big webbing belts about 6 inches wide brought the power down from the line shaft and turned it at right angle for the loom. It was all open gears and shafts. The guards were just a gesture, the whole thing was a safety nightmare. The drive belts ran on flat wheels. The belts would stretch in service and sometimes they would break. In either case we would cut ends with a knife, make holes in the ends and then lace them together with a strip of leather. Once the belt was rejoined, you flicked it up onto the wheel on the rotating line shaft, turned it 90 degrees (in the right direction) and then quickly flicked or spun it onto the wheel on the end of the loom. All this was done without stopping the line-shaft and was desperately dangerous. It would never be permitted these days.

Like all the machinery in the factory, the looms were very old, dating right back to the early days of the industrial revolution. They were built from steel, cast iron, wood and leather. Gear wheels were held onto shafts by tapered keys and of course, any nuts and bolts were Whitworth thread. There were a surprising number of adjustments that were possible. Adjusting the length of the picking stick would affect the speed of the shuttle and adjusting the picking strap would affect the speed and performance of the shuttle. Wrong adjustment could mean the slow shuttle being trapped in the warp when the loom came forward, or adjustment the other way could result in the shuttle becoming airborne and missing the box at the other end. The wood partition that separated the weaving shed from the mill bottom was covered in neat 3 inch square holes where these steel-tipped wooden projectiles had smashed through.

A large part of the weaving shed had previously been partitioned off; it was a separate room, brick walls and a very large heavy sliding door that was normally padlocked. It was opened on rare occasions when a well-dressed chap came in a big fancy car from Yorkshire. In this part of the shed were kept the Jacquard Looms. The visitor from Yorkshire would bring boxes of punched cards all precisely strung together and carefully folded into the boxes. A specialist weaver; a retired lady from up the greens was called in to work the looms. The cards were automatically taken into the loom and told it what to do to create patterns.

After the long and wide wool cloths came off the loom they went for carburising. This was done in a particularly derelict and almost sinister part of the mill that was unlocked about twice in a month when this job had to be done.

In the first room there was a big stone tank about 6ft square and about 30 inches high. Assembled above the tank, at about head height, there was a wooden roller. The tank was 60% filled with water, then acid, double strength and like thin syrup was added to the water to the correct sg. (measured with a simple hydrometer which was probably the most advanced piece of equipment in the whole factory). The acid was lethal. It came in large glass carboys, packed in straw in wire baskets.

We put the long piece of wool cloth into the tank and pulled one end over the roller. We then stitched the two ends together using wool thread. The roller was set in motion and the loop of cloth would go round and round ensuring that the acid solution was thoroughly into every fibre. Apparently the wool is unaffected by the acid but all other impurities are 'carburised'. After the correct time we took the cloth out carefully folding it onto a hand cart and then wheeled it into the drying room.

The drying room was about 25 feet long and was full of a system of steam pipes and rollers. The wet cloth was stitched to the end of the last piece that had been delivered earlier; it was on the floor and was slowly feeding in at ground level. The cloth went slowly on its way, looping backwards and forwards through the steam pipes and going upwards about 18 inches with every loop.

Just below ceiling height, the dry cloth was slowly emerging and being automatically folded onto a big wooden bench to wait its turn to go in the box.

The box was a bit like a small garden shed or more like a small outdoor toilet. It was constructed out of very heavy wood. The door opened to reveal a very polished interior and a strange system of odd shaped rollers on the back wall. We would put the cloth on the floor and pull one end up through the rollers, then pull it to the front and stitch the two ends together. The machine was the set in motion and the loop of cloth rattled round and round with the rollers hammering away at it.

The effect was quite remarkable. After a short time you could reach down into the bottom of the box and pull up handfuls of the carburised remains of twigs and other things that the sheep had picked up around the countryside.

Next the cloth went into the mill bottom where it was washed, hammered, dried, raised and dyed. Jack Ashworth and Dick Green sloshed around the mill bottom where the floor was always several inches deep in mysterious substances. The only substance I can really remember was Fullers Earth which Dick Green mixed in a large stone bath. There were several of these stone baths, each about 3 feet x 2 feet x 2 feet and carved out of a single stone.

Each piece of cloth had to be put in the stocks. The stocks were troughs set into the floor, each with two enormous hammers swinging in them. The hammers were raised by cams on a shaft and they would free-fall and pound the cloth against the end of the trough. Buckets of strange substances including Dick Green's Fullers Earth were added during the process and after a suitable period of time the cloth was removed. We were to pee in the stocks whenever they were working. I never really understood what this was about; most of the men took advantage of the facility when available. The stocks all had cast iron name plates on and one I remember had been manufactured in 1876.

In the mill bottom, Jack Ashworth did the 'raising'. The material, again in a loop with the ends stitched together, travelled against the face of a huge drum that rotated in the opposite direction. The surface of the drum was covered with teasel frames. The teasels were delivered in big sacks. They could have been a cross between a thistle and a pine cone. They were very dry and covered all over with incredibly sharp barbs. I have no idea where they grew or what the plant must have looked like but you could see from the remains of the stalk that it must have been formidable.

The teasel frames were about 6 inches deep and 6 feet long. The teasels had to be cut to length and jammed in side by side between the top and bottom rails. Setting the teasels was another of old Dans jobs and he did it in his loft above the mill bottom. People rarely ventured up the steep stairs into Dans loft. The teasels were very sharp, unfriendly and difficult to handle.

From the mill bottom the finished material went to the warehouse to be cut, folded and packed for shipment. It was pure wool cloth, red or blue and it went exclusively to Argentina. The warehouse was the clean, dry and comfortable part of the mill. It was above the fire 'ole. The warehouseman was a fitness enthusiast and an amateur boxer. His assistant was a younger woman who always took great care over her appearance despite the 19th century environment in which she worked. The warehouse was a restricted area and the door was usually locked.

Tommy Spencer and Tommy Halliwell were the maintenance and engineering staff at 'the woollen'. They were both broad Yorkshire people. Yorkshire is of course, well known for the wool trade as Lancashire is for cotton. This woollen mill in Bacup in Lancashire was a bit out of place and I have often wondered if the two Tommys were Yorkshire expatriates who had been brought in for their expertise.

Tommy Halliwell knew every aspect of the business and on a day to day basis he was the organiser and administrator. Tommy Spencer spent all his time in the fire 'ole tending the boilers unless some special task required him to come out with his box of special hammers, bars, chisels and ancient spanners. There was not a trace of chrome vanadium. All of Tommys spanners had been created by forge and anvil. Generally they were 2 or 3 times the size of their modern counterparts.

Last time I was downt' shed end you could still see the place where the fire 'ole used to be. It's just opposite the iron gateway that leads up to the back of Springhill Villas. Tommy Spencer was a short, lightweight guy. He must have been only a little over 5 feet tall but very muscular. His great delight was when he had a roaring fire in one of the boilers. He would remove his shirt and enthusiastically shovel coal into the firebox. He would then get a 15 or 20 foot long rake and pull it backwards and forwards through the fire. His real place should have been in the depths of a battleship with the captain constantly shouting down for more steam.

Everyone wore clogs and you could hear people coming long before they arrived. You could tell who it was by the sound of their clogs on the cobbles or the flags. Everyone wore a brat that was made of the sacking from the wool bales and was tied around the waist with sisal string. The men wore a heavy shirt and waistcoat. To go home they would put a jacket and scarf, or if they had to call somewhere they might bring out a collar and two studs.

Click here to go to Home Page